Whole School Change

The greatest impact on student learning and achievement occurs not simply in a moment in time but through the integrity of the learner's experience over time. Learner-focussed schools and school leaders recognize the importance of creating a coherent experience for their students whereby learning deepens and becomes consolidated across many years. Regardless of the setting or student population, whole-school change is a critical factor in supporting student growth and achievement. This was dramatically demonstrated in Pass Christian, Mississippi where the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina could not wipe away the deeply rooted learning that students had experienced and the thinking skills they had developed over

The greatest impact on student learning and achievement occurs not simply in a moment in time but through the integrity of the learner's experience over time. Learner-focussed schools and school leaders recognize the importance of creating a coherent experience for their students whereby learning deepens and becomes consolidated across many years. Regardless of the setting or student population, whole-school change is a critical factor in supporting student growth and achievement. This was dramatically demonstrated in Pass Christian, Mississippi where the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina could not wipe away the deeply rooted learning that students had experienced and the thinking skills they had developed over  time, and which remain intact today and thrive long after the flood waters have receded.

time, and which remain intact today and thrive long after the flood waters have receded.

- Use the Minds of Mississippi documentary film (30 minutes) with the accompanying Leadership Guide to facilitate discussion and whole school change. The guide includes:

- guiding questions

- use of visual maps to organize collaborative thinking for change

- links to extensions including from the Student Successes with Thinking Maps book

Chapter 11: A First Language for Thinking in a Multilingual School

Stefanie R. Holzman, Ed.D.

“The Thinking Maps took the English language learner to the highest level of thinking . . . in a very simple way.”

Teacher

- Results from an inner-city school with students learning a second language while differentiating instruction with a common language

- Moving expectations to a higher level across a low-performing school

- Changing school climate and culture toward higher-order thinking and literacy development

Many of the teachers in this urban, inner city, K –5 school of 1200 minority students (85% of those entering with Spanish as their primary language) thought they were already getting the best out their students.

Breaking the Rules for Change

"But I already use graphic organizers in my class," was the cry from my staff. As a first-year principal, I was breaking the most basic rule in the book for new administrators. I was immediately changing the mind-set of the culture-the way we do things around here-and I was making all these changes rapidly. A dynamic set of tools for activating the mind and directly influencing performance, Thinking Maps® were included in these changes. This was not an easy thing to do. Many of the teachers in this urban, inner-city, K-5 school of 1,200 minority students (85°/o of whom were entering with Spanish as their primary language) thought they were already getting the best out of their students. As the newcomer to the school, I had expectations that students should be achieving at higher levels than current test results indicated.

With this experience of implementing Thinking Maps, I also now have a standard by which I can compare other professional development trainings and other changes I plan to promote at Roosevelt Elementary School. This standard includes implementing changes that successfully affect student academic outcomes, teacher learning, reflection, accountability, and the school climate as effectively as this common language for learning, teaching, and assessing. We now have this new standard in our school-including for our students-because we have a first language for thinking, whether it be in a first or second language for speaking and writing. This language will help us to think and act on complex problems-such as how to transform and continually grow in an inner-city environment-with the confidence that we will be able to see more clearly each other's thinking...

read the whole chapter (pdf)

Chapter 5: Closing the Gap By Connecting Culture, Language, and Cognition

Yvette Jackson, Ed.D.

We believe that literacy for urban learners is best developed when the teacher mediates the learning process by providing lessons that foster social interaction for language development and guide the application of cognitive skills that assist students in constructing and communicating meaning. The Thinking Maps are a core component...

- Pedagogy of Confidence in urban schools to develop cognitive mediation across cultures

and language - Revealing "codes of power" through using Thinking Maps® by students in underachieving

schools - Literacy results from urban school systems across the country

The Pedagogy of Confidence

Thinking processes are universal, and Thinking Maps help students transfer these cognitive skills across content areas and grade levels. Children are born understanding cause and effect. They know how to think sequentially. In urban settings where there may be historic underachievement, providing tools that enable teachers to build on the capacity of the students to think critically through instruction that provides them with the means to fortify their understanding, competence, and confidence results in students who are motivated to excel and do excel. It becomes part of the common culture of the classroom, of the school, and, as we have seen, of whole systems.

read the whole chapter (pdf)

Chapter 13: Becoming a Thinking School

Gill Hubble, M.A.

Through research, practice, personal discoveries, and many rich conversations, we made a multiyear commitment to integrating the thinking maps language into our community.

- The 10-year development of a whole-school, integrated thinking-skills approach in

New Zealand - Using multiple maps for scientific problem solving

- How Thinking Maps® changed collaboration, communication, and performance across

a K-12 single-sex girls' school

training, and implementing Thinking Maps would actually provide a basis of understandings about cognitive strategies in general. When I was the associate principal and later researcher and consultant for the school, I became aware that this foundation allowed other strategies to be used and in fact strengthened various combined approaches. Over time this allowed for autonomy for both teachers and students as they selected the best strategies to fit particular purposes. Students using Thinking Maps on their own is a start but is not the end point or long-term goal of becoming a thinking school.

read the whole chapter (pdf)

Chapter 12: Feeder Patterns and Feeding the Flame at Blalack Middle School

Edward V. Chevalleir, Ed.D.

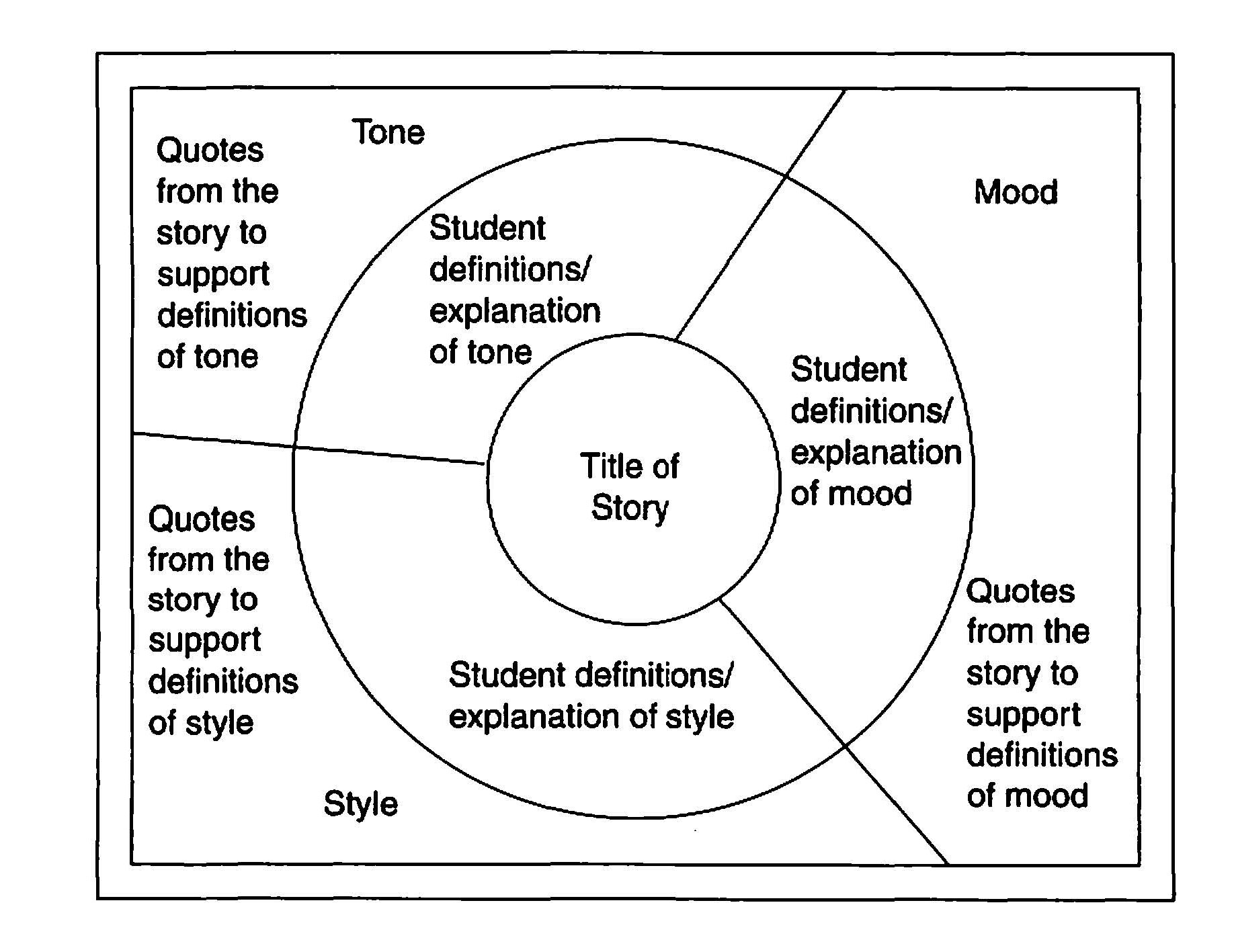

Thinking maps help students actively process information. The use of the maps creates immediate and specific questions. In a middle school classroom, the constant challenge is maximum engagement. Used in even their most limited form, thinking maps ensure eight “ready” questions—questions associated with each of the eight thinking skills.

- Uniting students from an elementary feeder pattern using a common language for

thinking and learning - Using Circle Maps and Frames of Reference for identifying author's tone, mood, and style

- Note-taking and thinking skills development using multiple Thinking Maps®.

After 10 years as a classroom teacher, I was offered two wonderful and challenging experiences, first as an elementary principal and then as a middle school principal. Through these positions I deepened my understanding of the complexity of instruction. I watched teachers lay a foundation for learning for elementary students, and as I entered my present position, I also saw that many of our middle school students needed a stronger foundation in skills to improve their learning that would stay with them throughout their educational and work careers.

After 10 years as a classroom teacher, I was offered two wonderful and challenging experiences, first as an elementary principal and then as a middle school principal. Through these positions I deepened my understanding of the complexity of instruction. I watched teachers lay a foundation for learning for elementary students, and as I entered my present position, I also saw that many of our middle school students needed a stronger foundation in skills to improve their learning that would stay with them throughout their educational and work careers.

My awareness of this deeper need grew over time from my classroom visits, walkthroughs, and supervision processes. I frequently heard frustrated teachers directing students to "take notes" as they were introduced to new information. I also heard my teachers lament that students didn't know "how to think" when they were challenged with new information and concepts. Over time I realized I couldn't recall any clear examples of explicit instruction in those two important areas-note-taking skills and thinking skills-even though teachers could well identify and articulate these problem areas.

From that day, over seven years ago, when I realized that the twin problems voiced by teachers about the lack of note-taking and thinking skills by students might be resolved through Thinking Maps, I never imagined that this focus on fundamental thinking processes as tools could, from the ground up, help transform our school into a much richer learning organization. It took perseverance as educators to see the forest of diverse students also as individual trees growing with common needs. This common language enabled a student with special needs, who was struggling with a task assigned by his teacher in another math class, to finally look to the teacher with a simple question: "Can I use a Thinking Map to get started?".

read the whole chapter (pdf)

Chapter 18: Thinking Maps: A Language for Leading and Learning

Larry Alper, M.S.Ed.

The ability of people to make meaning together, visualize the unknown, and formulate effective action is vital to the success of any organization. In today’s school environment, where change is not an event but an ever present reality, it is imperative that people develop the individual and collective capacity to process information, transform it into new understandings, and shape their futures.

- Facilitating constructivist conversations and engagement across a whole school

- A Circle Map and Tree Map for creating a unified understanding and deeper communications

within a faculty - Linking leadership and learning using Thinking Maps® for school-wide transformation

Explicit Thinking"), analyzing and applying data, engaging diverse stakeholders in essential conversations at the school and community level, and more. They have been used by teacher leaders and administrators to actualize the potential of professional learning communities by enabling all members of the school community to skillfully participate in and contribute to the processes associated with professional learning communities. We have been collecting data

from these experiences and the subsequent work done with the maps in the field by a variety of practitioners. The research has primarily been in the form of surveys, site visits, and interviews. We have used these methods to uncover and articulate the degree to which this particular work with Thinking Maps, as a navigational tool for leading, has had an impact on the learning and decision making throughout the community of the school and system and, ultimately, on student achievement.

Maps promotes curiosity, thinking in action, and collaboration. They give us the confidence to embrace complexity and deepen our appreciation for each other's ideas and experiences.

On the most fundamental level, Thinking Maps help us to have the conversations that truly make a difference in how we think and in what we are able to do with our ideas. In the context of the profusion of challenges we face as educators, these tools are essential to the pursuit of our collective ideals and aspirations. "All we can do," wrote Greene (1995), "is cultivate multiple ways of seeing and multiple dialogues in a world where nothing stays the

same."

read the whole chapter (pdf)