In the early 1990's David Hyerle, the developer of Thinking Maps, trained over 200 teachers in the Jackson Public Schools in Jackson Mississippi. He worked across many schools and in depth with small cadre of teachers as they applied Thinking Maps in their daily classroom teaching and for meeting "the standards" at that time. As a introduction to "Visual Tools for Constructing Knowlege" (ASCD, 1996), David chose to introduce readers to the maps and the emerging use of visual tools through Norm Schuman's work using the maps with students in his middle school social studies/history class in Jackson.

In the early 1990's David Hyerle, the developer of Thinking Maps, trained over 200 teachers in the Jackson Public Schools in Jackson Mississippi. He worked across many schools and in depth with small cadre of teachers as they applied Thinking Maps in their daily classroom teaching and for meeting "the standards" at that time. As a introduction to "Visual Tools for Constructing Knowlege" (ASCD, 1996), David chose to introduce readers to the maps and the emerging use of visual tools through Norm Schuman's work using the maps with students in his middle school social studies/history class in Jackson.

Below are just a few pages from David's book which was distributed to all 115,000 A.S.C.D. members in 1996 and sold more than 25,000 more copies—a groundbreaking book in the field. This book was revised from David's 1993 doctoral dissertation completed through UC Berkeley and Harvard Schools of Education. His new, completely revised edition with new research was recently published by Corwin Press in 2009, titled "Visual Tools for Transforming Information into Knowledge" (preface by Robert Marzano; prologue by Art Costa)

Read more about the book including the very comprehensive Table of Contents.

From Visual Tools...

Peek into Norm Schuman's 6th grade social studies classroom in Jackson, Mississippi, and you will see groups of students huddled over books, working together. They are sketching out a picture of information, drawing to the surface essential knowledge that was once bound by text. The students' writings and accompanying maps hang on string that spans the room. The writings and maps also are pinned to display boards in the classroom and hallway, and they are tucked into portfolios in an accessible corner.

Norm Schuman is a highly energetic man, quick with a smile or an idea. Norm might seem to be the kind of teacher who motivates students to learn by his sheer will and endless positive energy. But the truth is, he gives his students assignments that move him quickly to the background. Students have the tools for achieving what he assigns. They are in the foreground, and Norm is the patient sidelines coach.

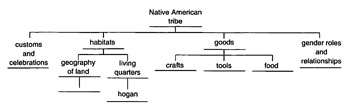

Today, each of six cooperative learning groups has been asked to read a passage from well-worn texts, on a different Native American tribe. Their task is to identify critical information about each group: customs and celebrations, habitats, foods, gender roles and relationships among members, and spiritual beliefs. Norm emphasizes finding details about each of these topics, along with the fact that he will create the final test questions from the information each group presents.

All groups use a common visual tool-a hierarchical structure-to collect, analyze, and synthesize the text into a clearly defined picture of a tribe. Each group will then share this picture in an oral presentation, using the map as a visual guide on the overhead projector.

Norm methodically moves around the room and looks down at the developing maps, guiding here, scanning there, nodding quietly in agreement at another table. Students' eyes focus intently on their group maps. The groups redraft these maps several times during two periods of instruction until only the most essential ideas have been distilled and organized from the text. In each group, a member takes a colored pen and copies the agreed-upon version onto a transparency page while the other members discuss the rotation they will use for the presentation.

The following day, oral presentations begin. Each group moves to the front of the room, placing a colorful transparency on the overhead. Then each group member speaks about a key point of interest from one area on the map. Their peers are busy at their seats, listening, sketching out the map, and making notes and comparisons to their own work.

Norm is in the back of the room, occasionally reinforcing a certain idea or, when necessary, offering a clarification or correction. But most of the time, Norm asks questions of a higher order. His queries are complex in that each requires students to make inferences from data they have woven together. He asks questions that involve comparisons between tribes. Synthesizing questions require students to construct generalizations; interpretive and predictive queries explore how certain tribes might have reacted to interventions from outside forces. He encourages students in the classroom to ask questions. As each group presents its work, however, Norm jots down new questions he had not thought of in previous years, questions sparked by these student presentations.

Days after the presentations are over, Norm gives the students a test. It includes questions based on text information they presented and questions that require them to have linked information from several of the hierarchy maps. He also asks questions that involve the use of other visual tools, such as those for comparing tribes, showing the development of a culture, or explaining the causes and effects of outside interventions. Students are ready for such questions because these tools have become a common way of communicating.

When asked about this process, and especially about the level of his questions-answered by students who have come into his classroom as supposed "underachievers" from low socioeconomic neighborhoods—Norm responds: "I could never have asked these questions of my previous students, most of whom came into my class several years behind in grade-level reading. I didn't give them the tools to make inferences like this. They didn't have the organizational abilities to work with so much information." Norm adds without hesitation that his current students now score higher on his exams than any previous class. Norm smiles, his eyes aglow with a sense of accomplishment: "And I am asking much more complex questions!"

Read more about the book including the very comprehensive Table of Contents.